A few months ago, I start moving my Javascript code from an Oriented Object/unorganized code to something much more close to Functional Programming. In this paradigm, I found interesting concepts such as immutability and high order functions…

And later on, colleague submitted a pull request with a javascript loop (plain old “for”). I suddenly remember how far was my last loop in Javascript…

Let’s start from the beginning, with the following data and a simple function:

var heroes = [ { name: 'Wolverine', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Deadpool', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Magneto', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: true }, { name: 'Charles Xavier', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Batman', family: 'DC Comics', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Harley Quinn', family: 'DC Comics', isEvil: true }, { name: 'Legolas', family: 'Tolkien', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Gandalf', family: 'Tolkien', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Saruman', family: 'Tolkien', isEvil: true },]

function stringifyHero(hero) { var heroStatus = hero.isEvil ? '😈' : '😇' return `${heroStatus} ${hero.name} (${hero.family})`}

// usagestringifyHero(heroes[0]) // "😇 Wolverine (Marvel)"The goal is to create a new squad of Heroes which are good and not from DC Comics. I also want to stringify each one.

The plain old loop way

With a loop the code should be like this:

var heroCount = heroes.lengthvar squadAlpha = []for (var i = 0; i < heroCount; i++) { if (!heroes[i].isEvil && heroes[i].family !== 'DC Comics') { heroes[i]['tostring'] = stringifyHero(heroes[i]) squadAlpha.push(heroes[i]) }}I see 3 problems here:

- after my loop, my data are altered. After the loop, the

heroesvariable doesn’t represent heroes anymore. It breaks the S from SOLID. - this code isn’t “thread-safe”. What happens if you want to use your heroes during the loop? With this kind of code, it can be risky to parallelize tasks.

- there are already 2 levels of indentation. Adding the third rule will probably add another level of indentation.

We call this approach: imperative programming. We explicitly declare how to get what we

want, step by step.

Otherwise, we have the declarative programming. It consists of focusing on the what, without

specifying how to get it…

Array.map and Array.filter to the rescue!

In a few words:

- Array.map: browse an array and apply on each element;

- Array.filter: filter an array.

Now the same code with these two high order functions:

var squadAlpha = heroes .filter(function (hero) { return !hero.isEvil }) .filter(function (hero) { return hero.family !== 'DC Comics' })// [Object, Object, Object, Object, Object]

var squadAlphaStr = squadAlpha.map(function (hero) { return stringifyHero(hero)})//["😇 Wolverine (Marvel)", "😇 Deadpool (Marvel)", "😇 Charles Xavier (Marvel)", "😇 Legolas (Tolkien)", "😇 Gandalf (Tolkien)"]If I don’t need squadAlpha variable, we can chain everything:

var squadAlphaStr = heroes .filter(function (hero) { return !hero.isEvil }) .filter(function (hero) { return hero.family !== 'DC Comics' }) .map(function (hero) { return stringifyHero(hero) })// ["😇 Wolverine (Marvel)", "😇 Deadpool (Marvel)", "😇 Charles Xavier (Marvel)", "😇 Legolas (Tolkien)", "😇 Gandalf (Tolkien)"]Now hero object isn’t changed and heroesExtended is a copy of hero which contain a new property.

Embrace the power of ES6 (or es2015)

First of all,

it is recommended

to drop the var keyword in favour of const.

Then, if you think that anonymous function reduces visibility and are redundant, I’ve got good news!

ES6 bring something call

Arrow functions,

a shortness way to write functions.

const squadAlphaStr = heroes .filter(hero => { return !hero.isEvil }) .filter(hero => { return hero.family !== 'DC Comics' }) .map(hero => { return stringifyHero(hero) })// ["😇 Wolverine (Marvel)", "😇 Deadpool (Marvel)", "😇 Charles Xavier (Marvel)", "😇 Legolas (Tolkien)", "😇 Gandalf (Tolkien)"]It’s nicer… but we can also go deeper with implicit return (drop the curly braces):

const squadAlphaStr = heroes .filter(hero => !hero.isEvil) .filter(hero => hero.family !== 'DC Comics') .map(hero => stringifyHero(hero))

// ["😇 Wolverine (Marvel)", "😇 Deadpool (Marvel)", "😇 Charles Xavier (Marvel)", "😇 Legolas (Tolkien)", "😇 Gandalf (Tolkien)"]Now, this code is thread-safe, the initial data aren’t altered and overall: it’s much more readable. ❤️️

Note: with an arrow function, you can also forget this ugly hack: var self = this. In fact, it

did not bind the this. When you write a function with the function keyword, this function

redefines 4 things (this, arguments, new.target and super). With the arrow function, it redefines

none of them.

Not enough?

Array.find

I also enjoy Array.find. You can use it like this:

// instead of:let searchedItemlet i = 0while (typeof searchedItem === 'undefined' && heroes[i]) { if (heroes[i].name === 'Gandalf') { searchedItem = heroes[i] } i++}

const searchedItem = heroes.find(h => h.name === 'Gandalf')// Object {name: "Gandalf", family: "Tolkien", isEvil: false}Array.reduce

Another function is always present when we speak about Functional programming & high order function: Array.reduce

const squadHeroes = [ { name: 'Wolverine', family: 'Marvel', ennemiesKilled: 4 }, { name: 'Magneto', family: 'Marvel', ennemiesKilled: 8 }, { name: 'Charles Xavier', family: 'Marvel', ennemiesKilled: 15 }, { name: 'Batman', family: 'DC_Comics', ennemiesKilled: 16 }, { name: 'Harley Quinn', family: 'DC_Comics', ennemiesKilled: 23 }, { name: 'Gandalf', family: 'Tolkien', ennemiesKilled: 42 },]

// beforelet squadScore = 0for (let i = 0; i < squadHeroes.length; i++) { squadScore += squadHeroes[i].ennemiesKilled}

// afterconst totalScore = squadHeroes.reduce( (accumulator, current) => accumulator + current.ennemiesKilled, 0,)It can also be useful for creating a custom object from an array of object:

const squadFamilies = squadHeroes.reduce((accumulator, current) => { if (typeof accumulator[current.family] === 'undefined') { accumulator[current.family] = 1 } else { accumulator[current.family]++ } return accumulator}, {}) // Object {Marvel: 23, DC_Comics: 2, Tolkien: 1}Array.sort

Then sorting an array is also common in JS. In this case, we use Array.sort.

const squadHeroesSortedByName = squadHeroes.sort( (currentHero, nextHero) => currentHero.name > nextHero.name,)Array and Immutability

It isn’t recommended to alter the original object. But if we need to update it (add a property for instance), you should work with a copy of this object, to keep the original one immutable. Object.assign is fine for cloning, and it works like this:

var originalObj = { prop: 1 }var copy = Object.assign({}, originalObj)obj.prop = 42console.log(copy) // { prop: 1 }originalObj === copy // falseSo in our case, adding a new property will produce a code like this (we need to copy each object):

const heroesExtended = heroes .map(hero => Object.assign({}, hero)) .map(hero => { hero.toStr = stringifyHero(hero) return hero })Set theory: union (∪), intersection (∩) and difference (∖)

If you want to deal with unique items, you should use the

Set object.

It takes an iterable object as a parameter (such as an array). Then to convert a Set to a classic

array, we use the

spread operator (...iterable).

const exampleSet = new Set([1, 2, 3, 1])exampleSet.size // 3. On instantiation, the duplicated entry was removed (here 1)

// To transform a Set object into an arrayconst exampleArray = [...exampleSet] // [1, 2, 3]Let’s take the previous example and see how do it in JavaScript!

const heroes = [ { name: 'Wolverine', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Deadpool', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Magneto', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: true }, { name: 'Charles Xavier', family: 'Marvel', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Batman', family: 'DC Comics', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Harley Quinn', family: 'DC Comics', isEvil: true }, { name: 'Legolas', family: 'Tolkien', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Gandalf', family: 'Tolkien', isEvil: false }, { name: 'Saruman', family: 'Tolkien', isEvil: true },]

const tolkienHeroes = heroes.filter(h => h.family === 'Tolkien')const evilHeroes = heroes.filter(h => h.isEvil === true)

const tolkienHeroesSet = new Set(tolkienHeroes)const evilHeroesSet = new Set(evilHeroes)If you cannot reminder what is the Set theory, here’s a schema:

// Union: tolkienHeroes ∪ evilHeroesconst union = new Set([...tolkienHeroesSet, ...evilHeroesSet])

// Intersection tolkienHeroes ∩ evilHeroes (element which are both in tolkienHeroes and evilHeroes)const intersection = new Set([...tolkienHeroesSet].filter(h => evilHeroesSet.has(h)))

// Difference tolkienHeroes ∖ evilHeroes (objects from tolkienHeroes which are not in evilHeroes)const difference = new Set([...tolkienHeroesSet].filter(h => !evilHeroesSet.has(h)))Notes:

- if the 2 arrays are built from different API, your object will probably not share the same

reference. I mean

tolkienHeroes[y] === evilHeroes[y]. In this case, your Set should only contain the object’s id (to ensure unicity). - the Set Object keep the objects references (no copy will be created on instantiation).

// I update an object propertyheroes[7].name = "Gandalf the white"[...tolkienHeroesSet].find(h => h.name === 'Gandalf') // undefined[...tolkienHeroesSet].find(h => h.name === 'Gandalf the white') // Object {...}

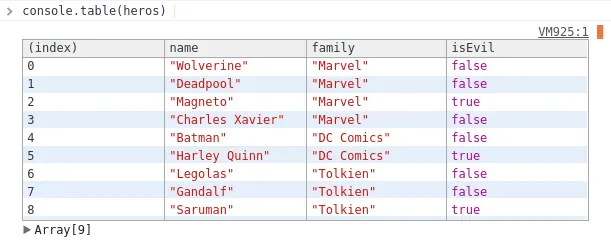

Bonus: console.table

When working with array, you can debug your array in something much more nicer than console.log:

console.table (you can click on the header to sort the data).

About the author

Hey, I'm Maxence Poutord, a passionate software engineer. In my day-to-day job, I'm working as a senior front-end engineer at Orderfox. When I'm not working, you can find me travelling the world or cooking.

Follow me on Bluesky