Last month, I gave a talk about

Immutability for functional JavaScript in the DublinJS meetup (slides).

I discovered Immutability almost 2 years ago in a French Meetup dedicated to Functional Programming

but I didn’t gave a try. 6 months later, after another talk, I decided to learn and understand this

paradigm. It changed my way of writing code, mostly, when I started to adopt Immutability as a rule

of thumb.

Immutability? What’s that?

If you follow the JavaScript trends, you probably heard about functional programming. It’s getting popular since the ES2015 version of JavaScript. Immutability is one pillar of this paradigm. The notion behind is very simple: “Forget about variables, everything is a constant”. You’re manipulating a list of users? Put them into a constant. You want to add an users? The list must be another structure.

var heroName = 'Logan'heroName = 'Groot' // 🚫 Unauthorized!Why Immutability is important?

Unwanted mutations

Let’s take our first example with Moment. Moment is a really nice library to manage your date in JS. The first time I was using it, I fall into a classic trap: an unwanted mutation.:

const today = moment()const nextYear = today.add(1, 'years')

today === nextYear // trueBy mistake -and because I didn’t read the full documentation :) - I changed the value of today (see last line).

Mutables variables give you headache

Mutable state is the new spaghetti code

— Rich Hickey, author of Clojure

Given a function hulkify() in a Hero class like the following one.

class Hero { constructor() { this.color = 'beige' this.strengh = 1 }

hulkify() { this.color = 'green' this.strengh = 1000 }}and a code like this:

const bruceBanner = new Hero()// ... do something ...bruceBanner.goToRestaurant()// ... do something ...bruceBanner.hulkify() // bring mutation// ... do something ...bruceBanner.fight()The previous examples bring severals problems:

- after mutation, the variable’s name and her associated values doesn’t match anymore. After

bruceBanner.hulkify(),bruceBannerbecame Hulk. For a better readability/maintainability, it deserves it own variable. - what if I reorder the functions calls? Then, I will send Hulk in a restaurant and the Human version of Bruce Banner in a fight…

If data have some mutations, you have to keep in mind the mutation order.

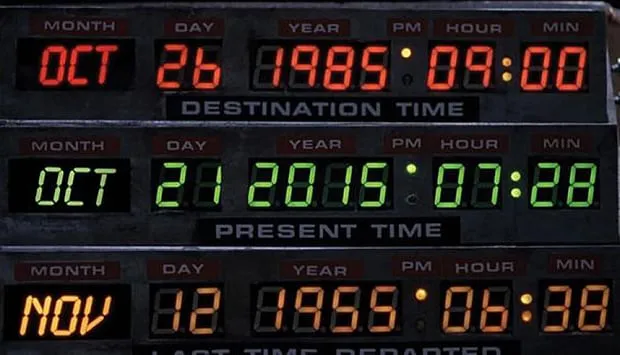

Time traveling

There is a really nice pattern called CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation). The starting point is the following: editing something may be harmful. Because mutation hide change. So this pattern consist in removing any update/delete statement only create. If you take a look, that exactly how Git works. If you delete some code, you can retrieve it later.

const heroPet[] = 'cat'hero.play(heroPet[heroPet.length - 1])// laterconst heroPet[] = 'dragon'hero.play(heroPet[heroPet.length - 1])This approach will allow the hero to play with his previous pet, even if he change it!

Thread safety?

One last advantage for moving into immutable object is the Thread safety. On a multi-threaded application, two threads can manipulate 2 different versions of one data structure. However, JavaScript is concurrent by default, so we’re not really impacted by this aspect (I didn’t try with parallel.js).

Pitfalls & Misconceptions

const is not about immutability

ES2015 came with a new nice keyword: const.

Constants are block-scoped, much like variables defined using the let statement. The value of a constant cannot change through re-assignment, and it can’t be redeclared.

— MDN

It means, once a constant is declared, you cannot change it.

const meaningOfLife = 42meaningOfLife = 'boom' // Uncaught TypeError: Assignment to constant variableThen came a big confusion on the internets. People start to think that const was made for

immutable structures. In fact const only create an immutable binding between the identifier and

the value. If you assign an object as a value, you’re free to change this object.

const hero = { name: 'Batman'}

hero.name: 'Daredevil'

console.log(hero) // Object {name: "Daredevil"}The object signature is still the same, only his parameters change. But it’s not an excuse for not using it!

mutable states inside map()

To loop an array, forget about for/while loop and start using Array.prototype.map(). Array.prototype.forEach() is a sibling to map() but it create side effect, while map prevent them by creating a new structure. Now, map() looks cool right? I can do some operations with my objects in a Array.map() loop, and it will preserve my initial values? Well… not exactly!

const newHeroes = heroes.map(h => { h.name = h.name.toUpperCase() return h})

console.table(newHeroes) // newHeroes now contains name in uppercase 👍console.table(heroes) // heroes now contains name in uppercase 👎As expected, I created a new structure of heroes with a toString property.

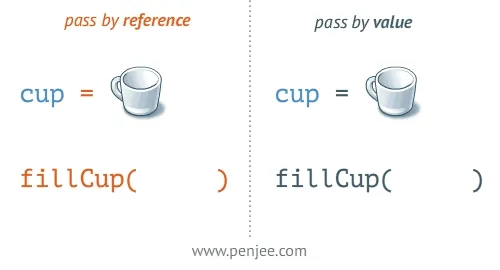

But JavaScript always pass variables by value… except when this variable refer to an object. And

almost everything is an object in JS! In the map() loop, h refer to a hero reference. That why the

heroes are updated!

Solutions

Hopefully, JavaScript offer severals quick wins to deal with immutability. To keep everything consistent, I’m gonna use the following structure for this functions:

const hero = { name: 'Daredevil', location: { city: 'New York', district: 'Kitchen Hell', },}Object.freeze() vs. Object.seal() vs. Object.assign() vs. Object Spread Properties

-

Object.freeze(): freeze the given object (only the first level)

Object.freeze(hero)hero.name = 'Jessica Jones'console.log(hero.name === 'Jessica Jones') // false (hero is unchanged)hero.location.city = 'Dublin'console.log(hero.location.city === 'Dublin') // true (hero.location has been changed) -

Object.seal(): prevent adding new properties to a given object

Object.seal(hero)hero.weapon = 'staff'console.log(hero.weapon) // undefined (hero is unchanged)hero.name = 'Jessica Jones'console.log(hero.name === 'Jessica Jones') // true (hero.name has been changed) -

Object.assign(): create copy of a given object

const newHero = Object.assign({}, hero)newHero.name = 'Jessica Jones'console.log(hero.name === 'Jessica Jones') // false (hero is unchanged)newHero.location.city = 'Dublin'console.log(hero.location.city === 'Dublin') // true (hero.location has been changed) -

Object Spread Properties - Stage 3 (Draft): an alternative to Object.assign() - currently in stage 3 (only available through compilers: Babel, TypeScript…).

const newHero = {...hero,name: 'Jessica Jones',}console.log(hero.name === newHero.name) // false (hero is unchanged)newHero.location.district = 'Dublin'console.log(hero.location.city === 'Dublin') // true (hero.location has been changed)

Whatever we use, we always face the same problem: we need a deep clone. Usually theses deep clone/copy methods use recursion.

And what about JSON?

When we Google the following term: Immutable + Javascript, some StackOverflow results redirects to JSON.parse(JSON.stringify()). At first sight, it could be interesting because it solves all previous problems.

const hero = { name: 'Daredevil', location: { city: 'New York', district: 'Kitchen Hell', },}const newHero = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(hero)) // "{"name":"Daredevil", {...}}"

newHero.name = 'Jessica Jones'console.log(hero.name === 'Daredevil') // true (hero in unchanged)

newHero.location.city = 'Dublin'console.log(hero.location.city === 'Dublin') // true (hero.location in unchanged)🎉 Tadaaa!

Well… I have a bad news: JSON for JavaScript Standard Object Notation* is a language agnostic format. Yes. Really!

It does not attempt to impose ECMAScript’s internal data representations on other programming languages.

— Final draft of the TC39 “The JSON Data Interchange Format” standard > (look at the introduction)

After, it’s makes sence. Ruby/Scala/Python/PHP/… should not implement some Javascript specificities such as Symbols, undefined… or even the functions!

How are handle non-stringifiable types?

They are simply removed.

const hero = { name: 'Daredevil', birthdate: new Date(1989, 4, 11), sayHello: () => 'hello', symbol: Symbol(), banana: undefined,}JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(hero)) // "{"name":"Daredevil", birthdate: "1989-05-10T23:00:00.000Z"}"How are handle circular references

Circular references simply generate errors.

const daredevil = { friends: [daredevil],}

JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(daredevil))// Uncaught TypeError: Converting circular structure to JSONSo for both of this reason, I would recommend to use this with an extreme precaution.

Persistent data structure

I now want to save the world against a big attack. Let’s grab my heroes. Yes, ALL of them!

const heroes = [ ⋮ { name: 'Wolverine', isReady: false, /* ... others properties ... */ }, { name: 'Deadpool', isReady: false, /* ... others properties ... */ }, { name: 'Magneto', isReady: false, /* ... others properties ... */ }, { name: 'Gandalf', isReady: true, /* ... others properties ... */ }, ⋮ (100 000 heroes)]Oops, I need them to get ready.

heroes.map(hero => { const newHero = Object.assign({}, hero) newHero.isReady = true return newHero})To update just one field, I have to create 100 000 copies of my objects. And also, duplicate a lot of unchanged properties, including the Hero Gandalf which is already prepared… We are going to face performances issues… there is probably a better way to do it!

If you have this problem, it’s time to switch to libraries such as Immutable.js or Mori

About the author

Hey, I'm Maxence Poutord, a passionate software engineer. In my day-to-day job, I'm working as a senior front-end engineer at Orderfox. When I'm not working, you can find me travelling the world or cooking.

Follow me on Bluesky

PHP et Programmation fonctionnelle

PHP et Programmation fonctionnelle